The common perception about a Film Editor’s job is that he is the person who makes the cuts. A Director captures a good deal of unnecessary information during the shoot and then the Editor chooses the correct shots, trims the extra material and sculpts the final film.

How true is that? An Editor does cut the recorded material. But that is not the only purpose of his job. Instead, he joins chunks of action shots and creates a scene with the shot-changes hidden. He chooses the emotion that suits the Director’s vision and makes it as effective as possible.

The Editor can be called a Director in disguise. He directs the film, but on the table. He does not shoot. He doesn’t even make an appearance at the shooting floor. But he is the first viewer of the shot material, known as the rushes. He recreates the film, with the screenplay in hand, to tell the story. He plays the role of the film’s first critic too.

We talk about a film’s internal rhythm that develops in time. More than the Director, it’s the Editor who creates that rhythm. It is difficult to describe that rhythm in words. But as the audience, we realize when successive shots become shorter and the scene gains pace. Such accelerated mood becomes a creative tool during a suspense-filled moment or a chase scene. Thrillers regularly use fast cuts so that the story moves on from one aspect to another, leaving little or no time for the audience to concentrate on the details. It creates a mood of rapidness, an emotion of tension.

Shots tend to become longer when it is time to introspect. Sometimes the scene demands a slow moving camera, where the frame just stays where it is for minutes. Filmmakers such as Theo Angelopoulos make good use of such stasis in time. A brilliant example was where the little girl is molested inside the truck at the end of Landscape in the Mist (1988). We, as the sympathetic audience, want the camera to move, to recede further away or to come closer, so that we can get rid of the tension and guilt. But the camera does not move. It remains stationary, at a distance from the truck where the crime is happening. It is an Editor’s choice to use a scene like that. It does not matter if the Director has actually chosen the shot. It is the Editor’s mind which is at work here.

(Image Courtesy: http://bit.ly/rTHPwZ)

In some ways, an Editor’s mind works like a musician’s. The Editor creates tempos throughout the film that sustain tension at particular points in the story. The ups and downs in the story act like musical notes which operate in time. Maybe that’s what Satyajit Ray meant when an interviewer asked him how he makes a film and he said, “Musically!”

So how did it all start? There was no Editor and no need for editing when movies were first born. The camera started and stopped only once throughout the entire film. Each scene was a shot, and that made an entire movie. The duration of such movies was limited to the capacity of film, which would hold not more than 100 ft at that time. More than 100 ft, and the film would become prone to tearing due to the stress produced by intermittent motion. That problem was solved with the introduction of Latham loop.

However, the problem with such one-shot one-scene set up is that the filmmaker cannot change point-of-view without changing the camera position during the shot. In the initial days, camera dollies were very primitive and jerky. Also it wasn’t always possible to change the camera position without damaging the flow of the story.

Hence, the films looked like recorded plays. In fact, most of them were exactly that – staged plays filmed from a typical theater audience position. They gave an impression of a third person point-of-view and the only way to focus the spectator’s attention to a part of the screen was to move character.

In 1903, British filmmaker George Smith carried out a highly successful experiment by changing the point-of-view in Mary Jane Mishap. He juxtaposed wide, establishing shots with medium close up of the characters, to make the audience empathize with them. Dividing a scene or sequence was tried even before that. Goerge Méliès attempted that in his film Journey to the Moon (1902).

(Image Courtesy: http://bit.ly/vGuYjr)

During the same period, Edison’s film company made two films that explored cinematic storytelling breaking them into sequences. Both the films, The Life of an American Fireman (1903) and The Great Train Robbery (1903), used the cross-cutting technique to portray simultaneity. Now the audience could see for the first time while an action was happening at one place while what was happening at another place during the same time. The concept of ‘Meanwhile’ was very effectively produced by the logical juxtaposition of scenes, connected through common cues by a set of conventions, later to be called parallel editing.

It was the filmmaker who chose these cuts. However, specialized people had to be employed soon for the purpose of physical joining of negatives of different scenes or shots. They rose in rank with time and started suggesting things to their boss. They were the world’s first Editors.

It was in 1903, when the first big close up (also known as insert) appeared in Edison Film Company’s short, The Gay Shoe Clerk, to offer a glimpse into a character’s psyche by shifting the point-of-view. A mini story was effectively told using only two shots and three cuts. Cinema had started in the magic tent. But now the magic went too far.

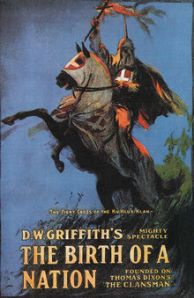

That year was indeed very auspicious for cinema. A young screenwriter called David Wark Griffith joined American Mutascope and Biograph Company that year, and twelve years later he would change the face of film making and establish cinema as modern art.

Griffith applied almost every possible camera technique from his time to make his first feature length film, Birth of a Nation (1915). Though he may not have invented the techniques himself, he was the first to show how narration in literature could could be applied to cinematic storytelling. He demonstrated how a shot could represent a sentence from literature. He showed the consistent way to cut and join shots to build an equivalent of a paragraph from literature and turn it into a scene in the movie, join scenes to build a chapter from a novel and create a sequence. Ever since Birth of a Nation, all filmmakers around the world, starting from Eisenstein in USSR, Bresson in France, Phalke in India and Hitchcock and John Ford in Hollywood, followed Griffith’s footsteps.

(Image Courtesy: http://bit.ly/vo30of)

Griffith was followed by a line of master Editors. They joined two shots and joined two lives which would otherwise remain separate. Movies still show two persons talking over telephones looking in opposite directions in different shots, so that their eyelines match. We still hide the shot changes in modern films depending on the action change; matching the two different shot magnifications. It is similar to a sentence change, or to the complexity of the sentence, depending on the change of the principal verb.

Editors make the movies lifelike. In life too, we want to cut the unnecessary parts from our memories, to erase the wastes of our folly and to make it focused and steady. Don’t we?

Filed under: Careers, Film Industry | Tagged: Careers, David Wark Griffith, director, editing, Editors, Filmmakers, Goerge Méliès, Griffith, he Great Train RobberyThe Gay Shoe Clerk, Journey to the Moon, Landscape in the Mist, Satyajit Ray, The Birth Of A Nation, The Life of an American Fireman, Theo Angelopoulos | Leave a comment »